Running makes you smart, period.

Several mechanisms make sure the right substances in your brain are released when you are running, synergizing to improve for instance memory performance. But how does this work?

Running is not only a relaxing way to pass time (… yes it is (1)), it can also boost your cognitive performance (2)! Several mechanisms make sure the right substances in your brain are released, synergizing to improve, for instance, memory performance. The gender-neutral paragraph below will tell you more about this. Interestingly, the effects may not be consistent across different phases of the menstrual cycle. The not-so gender-neutral paragraph elaborates on this hip topic.

The gender-neutral paragraph

Running at 60-90% of your maximal capacity makes your body release endocannabinoids: the body’s self-produced cannabis (2). This cool substance in turn makes several brain bits release brain-derived neurotropic factor, BDNF for short. What makes BDNF great is that it tells new cells to start growing, and existing cells to increase communication amongst each other. As such, it is helpful in memory formation and in the brain’s adaptations to your new healthy lifestyle.

Serotonin is important for emotional processing and memory, and dopamine is important for working memory, mental flexibility and the feeling of reward. Frequent running increases dopamine levels, but changes in serotonin activity are region-dependent, with some areas becoming more sensitive, and others less sensitive to serotonin signals.

In an effort to make science easy and straightforward, most current research has neglected to take the female hormonal cycle into account (if they take female participants at all). Unfortunately, science isn't easy and straightforward, and ovarian hormones interact with the messengers I previously described.

The not-so gender-neutral paragraph

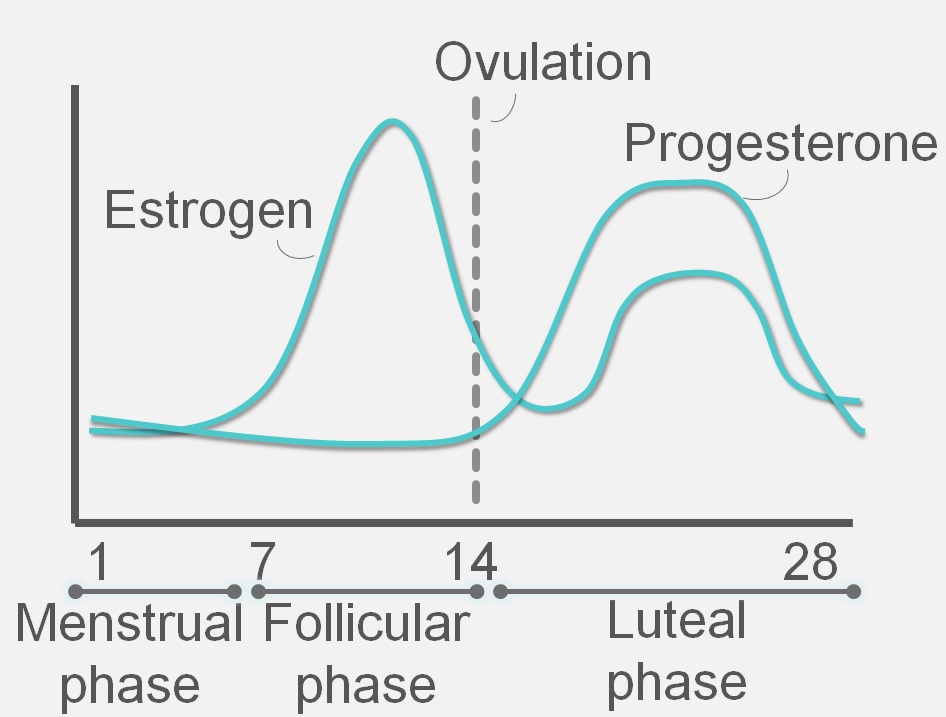

Let me introduce to you: Mandy, Fiona and Lucy, the ladies running in the picture at the top of this page. Combine this with the picture below to see that Mandy is crossing the red sea, with low estrogen and progesterone levels. Fiona is running in the Follicular phase, meaning her estrogen levels are high and progesterone is low. Meanwhile, Lucy is running in the Luteal phase, meaning her progesterone levels are high and her estrogen levels are quite high.

Lucy has the highest baseline BDNF levels, because progesterone and estrogen both increase its presence (3, 4). However, she won’t be as relaxed as Mandy and Fiona, because progesterone increases presence of an enzyme that breaks endocannabinoids down (2).

Pre-run, Fiona is in the best mood, as high estrogen levels interact with serotonin to improve mood (5). Mandy’s pre-run mood is the worst (no surprise there), but she may actually reap the greatest benefits from a run of all three ladies: running will elicit a relatively greater increase in serotonin levels, as her baseline is lowest, so her mood will improve the most post-run. In addition, the endocannabinoid-breakdown enzyme should be quite low, so a run will definitely relax her.

Fiona should have the highest pre-run levels of dopamine, as high estrogen levels concur with high dopamine activity (6, 7). This means she can probably run the farthest, since the drop in dopamine levels during the run is the moment exhaustion sets in.

At the risk making the interaction between ovarian hormones and these transmitters seem easy and straightforward

The gender-neutral bottom line: go run. Making the time for running will pay off with regard to mood and academic performance.

The not-so gender-neutral bottom line: go cross that red sea. You may not run far, but your run will feel great.

References

1. How to run away from your problems

2. Heijnen, S., Hommel, B., Kibele, A., & Colzato, L. (2015). Neuromodulation of Aerobic Exercise – A Review. Frontiers of Psychology, 6: 1890. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01890

3. Kaur, P., Jodhka, P. K., Underwood, W. A., Bowles, C. A., de Fiebre, N. C., de Fiebre, C. M., & Singh, M. (2007). Progesterone increases brain‐derived neuroptrophic factor expression and protects against glutamate toxicity in a mitogen‐activated protein kinase‐and phosphoinositide‐3 kinase‐dependent manner in cerebral cortical explants. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 85(11), 2441-2449.

4. Pluchino, N., Cubeddu, A., Begliuomini, S., Merlini, S., Giannini, A., Bucci, F., ... & Genazzani, A. R. (2009). Daily variation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cortisol in women with normal menstrual cycles, undergoing oral contraception and in postmenopause. Human Reproduction, 24(9), 2303-2309.

5. Amin, Z., Canli, T., & Epperson, C. N. (2005). Effect of estrogen-serotonin interactions on mood and cognition. Behavioral and Cognitive Neuroscience Reviews, 4(1), 43-58.

6. Colzato, L. S., Pratt, J., & Hommel, B. (2012). Estrogen modulates inhibition of return in healthy human females. Neuropsychologia, 50(1), 98-103.

7. Jacobs, E., & D'Esposito, M. (2011). Estrogen shapes dopamine-dependent cognitive processes: implications for women's health. The Journal of Neuroscience, 31(14), 5286-5293.

0 Comments